This is a chapter from It’s All About The Road, a collection of stories and essays which, together, tell a complete history of Stoke, from the Ice Age to thirty years from now, through stories from one road. This story was inspired by the death of a Polish pottery worked, Demetrious Myiciura, which is the only time in the UK vampires are mentioned on a death certificate. the real story happened in 1972, and this one happens around then. Much of the detail is real, what happened after Lidice is true, the house as described here exists and I’ve stayed in it, and the head on the penny was designed by somebody who lived a few doors up from it.

This is a chapter from It’s All About The Road, a collection of stories and essays which, together, tell a complete history of Stoke, from the Ice Age to thirty years from now, through stories from one road. This story was inspired by the death of a Polish pottery worked, Demetrious Myiciura, which is the only time in the UK vampires are mentioned on a death certificate. the real story happened in 1972, and this one happens around then. Much of the detail is real, what happened after Lidice is true, the house as described here exists and I’ve stayed in it, and the head on the penny was designed by somebody who lived a few doors up from it.

~~~~~

The rubber seals around the windows were cracked, and where the barrier was broken rivers ran down the curved walls each time the dark red bus turned its sides to the wind. The water pooled at the edges of the floor. It wasn’t the only water inside the double decker; the heat from the bodies had steamed the windows. So the world outside was filtered through two layers of water, thick rain outside and thin condensation inside. Like looking through the dirty lenses of old glasses, the world was grey and indistinct, occasionally details lurching into sharp focus. A tiled street name, Park Street, painted out in black. A masonic square and compasses carved in stone. Shakespeare’s face mosaicked in tiles. A tin sign advertising Spratt’s Canary Mixture, ‘Sold Only In Packets’. All fragments, a brief focus on a cinematic story happening, off camera, away from the lens of the bus window.

Better than the days after he first moved here, though. There was the blackout then. But smog too, and a man had to walk in front of the buses with a torch. The only thing that could penetrate the dark then were a pair of searchlights by the gates of the Michelin Factory up the road.

In the seat in front of him, a woman sneezed into a grey handkerchief. The cotton was frayed, and would never wash to clean white again. He realised that what he had thought to be a stain was an embroidered pattern of deep violet pansies which had faded to a different shade of grey. Each outbreak of sneezes was followed by a dry, rasping wheeze. She had sneezed three dozen times since he had got on. Thirty six sneezes, thirty six wheezes. Again – thirty seven. Each time the bus hit a pothole and shook, he reached for the handle on the seat in front of him, and his hand brushed against the thick, rough knitted wool of her coat. It was thick with damp, and under that, grease that had built up over years. Each time he brushed against her, he closed his eyes and flinched.

In the seat in front of him, a woman sneezed into a grey handkerchief. The cotton was frayed, and would never wash to clean white again. He realised that what he had thought to be a stain was an embroidered pattern of deep violet pansies which had faded to a different shade of grey. Each outbreak of sneezes was followed by a dry, rasping wheeze. She had sneezed three dozen times since he had got on. Thirty six sneezes, thirty six wheezes. Again – thirty seven. Each time the bus hit a pothole and shook, he reached for the handle on the seat in front of him, and his hand brushed against the thick, rough knitted wool of her coat. It was thick with damp, and under that, grease that had built up over years. Each time he brushed against her, he closed his eyes and flinched.

He got off a stop early, stumbling down the curved metal stairs, off the bus, relieved to be in the open air again. He didn’t mind the rain, or the cold, or the wind. He had grown up somewhere colder, and whenever he felt the chill he remembered, and thought himself lucky to have this new country. The winds at home had been harsher, the things he had seen worse than anything that could happen here. But even so after the forty years he had been here, it was still new, and often surprising, and still not home.

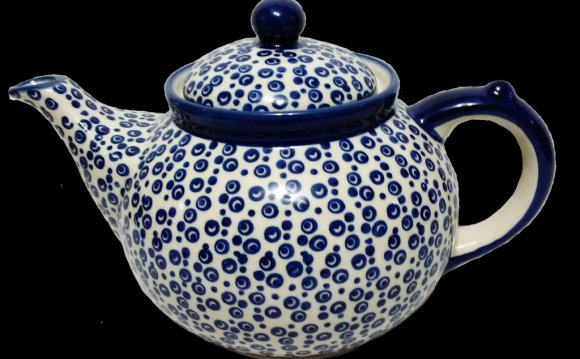

This town welcomed foreigners, and always had. He remembered, not long after he had arrived, meeting the children who had arrived here on the Czech Kindertransport. And the way that the miners here had raised funds to rebuild Lidice, after the Nazis destroyed that village. ‘Lidice Shall Live!’, Stoke had declared, and it had. But while Stoke was warm, and generous, it kept foreigners as foreigners, held them at a distance. The contradiction was at the heart of this place. The potteries were always bringing new people in, always embracing the new ideas, technology, skills they brought. The pottery where he worked was full of Germans at the moment, bringing new lithographic machines and transfer cutters. He avoided them.

Generation after generation of immigrants, but still Stoke stayed distinct, and cherished history and tradition, he thought, guarding its own local food and the rich dialect. He spoke Stoke’s English but still with a Polish accent. To the Englishman he met when in London for meetings, he sounded like a man from Stoke; to the locals, he sounded foreign. To theoccasional Pole he met at work, his Krajna dialect sounded archaic, full of forgotten words and old inflections. He knew he was adrift, a refugee, and had been for the past forty years.

Generation after generation of immigrants, but still Stoke stayed distinct, and cherished history and tradition, he thought, guarding its own local food and the rich dialect. He spoke Stoke’s English but still with a Polish accent. To the Englishman he met when in London for meetings, he sounded like a man from Stoke; to the locals, he sounded foreign. To theoccasional Pole he met at work, his Krajna dialect sounded archaic, full of forgotten words and old inflections. He knew he was adrift, a refugee, and had been for the past forty years.

The smell of baked bread was strong on the wind, and brought him back to the here and now. He remembered the last of the bread which he had burnt under the grill that morning. He had never mastered the grill and would lean forward watching the bread below the flickering gas flames. But he never judged it right. It had been a long time since he had tasted toast without a thin layer of burning, and his breakfast every day was like a burnt offering to an old god. He pushed through the heavy half-door of the bakehouse. As always, it pushed back, as if the shop didn’t want him to enter. Getting inside always felt like a small victory. He celebrated by buying a small loaf, and two scones. The bread here tasted faintly of the coal that fired the ovens, and for the second time, he remembered the place where he lived before. Bread baked in the kitchen that was the only warm room in a cold house. The room his wife so rarely left.

Distracted by the remembrance of his Yetta, his little home ruler, he hardly noticed he had stepped outside and then he was at the end of his road. The rain had pushed thick streams down the side of the rough dirt road. The rain remembered there used to be a spring here and was trying to find the fastest way down to the river at the bottom of the valley. Two thick pools stirred at each corner of his road, brought up short where dirt road met tarmac, and thin twigs twirled and twisted as they were caught in the contradiction. The pool on each side spun a different way, he noticed. There was some order behind the chaos of this small flood.